Where is Royce? Click to sail along! ⛵ .“Royce, get up.” My eyes shoot open. Why is Ella waking me up? And hasn’t anyone taught this girl how to nicely arise the crew? Her abrupt command could have woken the dead. “We’re here.” She said and then was gone, as quickly as she had appeared. We’re here? Where are we? What time is it? And then the blanket of sleep was gone. We’re here. We’re here! I leapt from bed, and landed like a cat on the sole floor - a maneuver I had now perfected having practiced thrice daily for nearly twenty days. Alejandro did the same, although his feline reflexes are more in line with Garfield at his advanced age. I glanced below my bunk - Odie was gone. We were the last two arriving on deck moments later. And there she was. Antigua. Her lush vegetation, dotted with brightly colored houses, was a clear giveaway that we had arrived in the Caribbean. “Smell that.” Mia said with a broad smile.

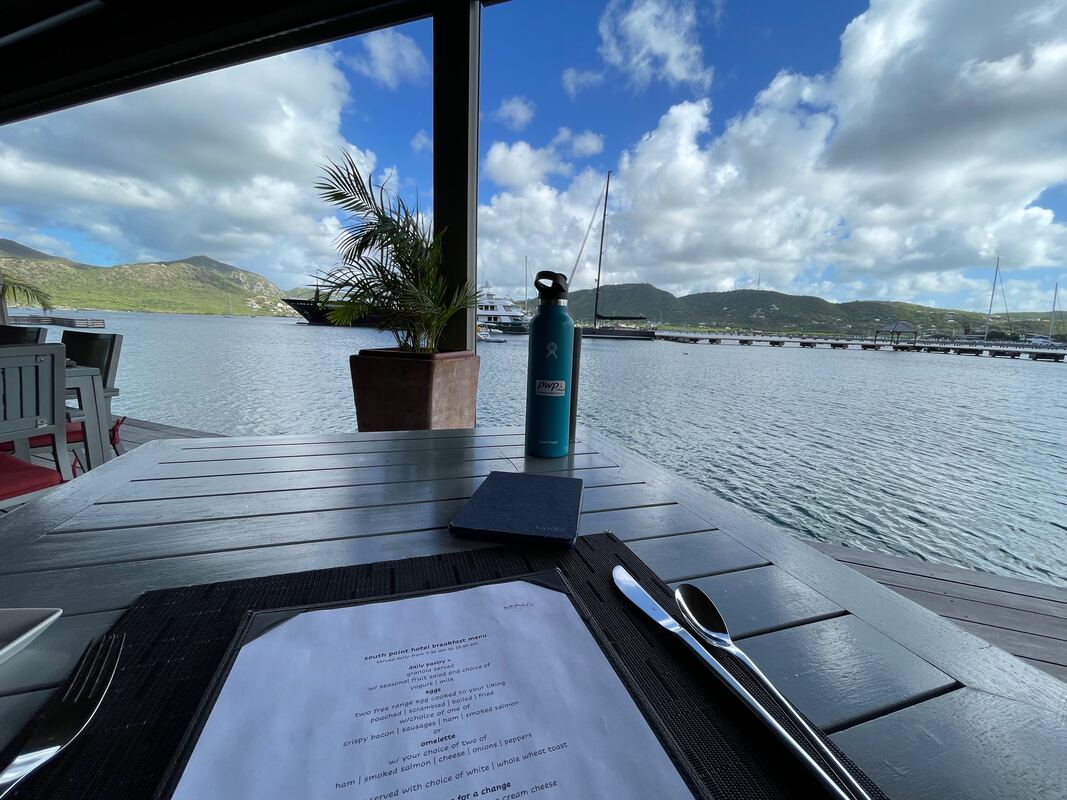

“Huh?” Wake up, Royce. “Smell that.” She repeated, her grin somehow growing wider. The rich aroma of…what is that, nutmeg? The standing joke in my house is that I have zero sense of smell. A Jewish nose that doesn’t perform - oh, the irony. But for the first time in nearly a month, it wasn’t the unmistakable foulness of the head, or Eau de Latino that my unsophisticated olfactory bulb recognized. You could smell the land. This rich, sweet, overpowering, delicious, warm aroma. My smile returned Mia’s. The pink light of dawn painted a backdrop to the island, no more than a couple miles off our starboard rails. I stared. We all stared. Nothing need be said. Even Staton was in silent reverie - a first since waltzing up to my table in Las Palmas. I grinned at him. He grinned back. We made it. We’re here. We slowly turned to starboard and entered the mouth of Falmouth Harbor, under motor. The yankee sail was quickly furled, and for the first time in 17 days, 19 hours, and 25 minutes we lowered the main. To bookend our journey, I once again climbed the mast, and helped guide Falken’s exhausted sail to her boom. The process of flaking (folding) the main back and forth across her boom took all of us, with the exception of Nelson, who was slowly keeping us out of harms way - several sailboats laid at peaceful rest throughout the harbor. Once her main was flaked and tied down, we fastened buoy’s to life lines, and lines to cleats, ready to hook ourselves to the dock. 10 minutes later, we were attached to land. The unrelenting motion underfoot we had grown accustomed to for a month was gone. The boat was still. I walked to the end of the pier, the longest continuous stroll I had taken since climbing aboard Falken in Spain. Come to find out, walking is like riding a bike. I hadn’t yet noticed any sense of sea legs. Perhaps I had left those at, well, sea. We gathered in the cockpit, not really sure what to do first, or how to feel. Mia emerged from the hatchway, her perma-smile distracting me from the objects in her hands. And then I noticed. And I smiled too. She had cups and a bottle of Champagne. Who is this party girl, and what have you done with that all-business mate from Sweden? Who is this stowaway? “Baruch atta adonai” and down the hatch. Three thousand, two hundred and twelve miles, and nearly a month since my last drop of alcohol, never mind that every beverage since Spain was either piping hot coffee or lukewarm tap water. The impact of chilled Champagne was immediate, but fleeting - I wanted off this boat to indulge in more icy cold adult beverages. So, with haste, I started tackling the list of to-dos, presented the night prior. I’m sure it came as a shock to the captain and crew that I knew how to work and was motivated to do so - had they uncovered the right “carrot” earlier in the passage, they surely could have extracted more from the lazy guy who chose sunbathing to sail trimming. But Red Stripe has a magical power to extract work from the most lethargic old salt. Both of which I had become somewhere out there with the drifting seaweed. For an hour, Staton and I sprayed and scrubbed, hosed and hauled, with the occasional stink eye toward those lazy crew glued to their phones who still thought we were drifting along on the Atlantic, with nowhere to go and nobody to see. And at the self-appointed hour of completion, I set down the hose and announced to little pageantry that I was done cleaning, and would now like to leave the boat. “We have to wait for Chris to clear us through customs - he’s not back yet” Mia explained with an equal measure of authority and trepidation - at this point, I could certainly walk away, no longer trapped by an inescapable ocean. “Hasn’t he been gone an hour already?” I questioned. “Customs can sometimes take 2-3 hours, Royce. It’s the Islands.” She clarified, with a hint of defeat in her voice. “Staton. Let’s go for a beer.” I shouted from the dock, my partner in crime avoiding the blazing sun belowdecks. And like a gopher, he emerged from the companionway, and joined me in the mutinous desire to find a bar sans passports. “You’re not allowed off the docks until we’re cleared.” Mia pleaded from the boat. “Mia, if this country is so unorganized that it takes them 3 hours to check our passports, I think it’s safe to assume they won’t expeditiously track down a couple uncleared sailors before we polish off a six-pack.” I explained in the nicest way possible, while making it clear that only an act of God was going to stop me from walking to a dockside bar and quenching my month’s-long thirst. In defeat, she made us promise to return when Chris was back. We’ll keep our eyes on the pier, we assured her. And so, with Nelson and his recently arrived bride Erica in tow, we headed to a sailor’s haven. It wasn’t until mid-way through my third Red Stripe and two glasses of water that I finally quenched my thirst. Which was timely, because Chris came strolling down the dock right at that moment, so we finished our beverages and joined the entire crew on the dock. Turns out, after telling our bartender Lenox we’d be back in a few hours that 5 minutes later we were sitting in the restaurant of the same establishment. Apparently an all-crew lunch takes precedence to letting us go free. “Another Red Stripe, Royce?” I was asked with a knowing smile. “Thanks Lennox. That was a fast three hours, huh?” I remarked with a laugh. He so gets me. After spending 3 weeks in close quarters, despite the lubrication provided by cocktails all around, the twelve of us (now with Erica as an honorary crew member) had nothing of any interest to discuss. A warm shower and air conditioning was awaiting me at a luxury hotel on the water not 100 yards away, and only my passport and this lunch was standing in my way. I scarfed down my meal, and stood up, indicating to everyone that we better visit the customs office before they close and we’re all forced to spend another night on the boat. In agreement, we quickly paid and walked nearly a mile, following Chris to customs. If I wasn’t half drunk, all the way tired, hot, sweaty, irritable and yearning for alone time, I might have enjoyed Nelson’s Dockyard more. This UNESCO historic 250 year old military outpost and cobblestoned streets was the epicenter of original Antigua and housed the customs office. Individually, we appeared before the magistrate, pleading our case for entry. No I do not have any fruits or vegetables to claim. Those were eaten 2,000 miles ago, and I definitely didn’t get the last apple, thank you very little. Please let me have my passport so I can be free of these savages and can collapse in my air-conditioned hotel room. 15 minutes later, I was emptying my duffel bag of moist clothing all over the deck of my very air-conditioned studio apartment overlooking the water. Another win from my now best friend and travel agent, Courtney. I had texted her from the boat a day prior and asked her to book accommodations at the nicest place she could find within a nine iron of the boat. Like Lennox, she so gets me. There was a quick dip in the pool, a nap, a shower, and a quick text to the group that I would be tasting rum at the bar before our 7:30 dinner reservation with the Falken crew. Vince took me up on the invitation, and humored me as I tried the local English Harbor rum. Lennox was of course very helpful in guiding me on a brief journey through the local spirits. With the wheels greased, we walked to another all-crew event. Don’t these people have other friends? While I had been recuperating from the afternoon’s shenanigans, Alejandro and Staton had apparently discovered the swim up pool bar of their hotel and had not slowed down their thirst-quenching pursuits. I was shocked to see that Staton’s 6-month and as many inches-long beard had disappeared. “Dude. What the fuck happened to you?” I asked in shock at this baby-faced baboon with a shit-eating grin on his face. “I went to shave today and messed up. So I took it all off.” He responded, smiling. “Where is Alejandro?” “He’s still passed out.” Jesus. I leave these two ass-clowns alone for three hours, and the wheels fall off. Unlike lunch, we were all laughs and obnoxiously enjoyed one last round of sharing our ups and downs. The drink of the night was an Old Fashioned Rum Punch, which helped everyone loosen up and provide some lively take-aways, “suggestions”, and general learnings from the cruise. Even Vicky was animated - but Canada hasn’t yet discovered rum, so her behavior should be excused. Mid-dinner, our sauced little Costa Rican also showed up, all smiles and giggles. Heaps of praise were thrown, justifiably, on our captain and first mate. Chris scored positive feedback for his wealth of knowledge, leadership, and dry sense of humor. Mia’s accolades included her positive energy that Nelson highlighted really came alive when the rest of us were going into our darkest depths of misery late in the voyage. Her culinary skills earned equal praise - I mean, who bakes fresh scones in the middle of the Atlantic?! And Ella. Well, she was the intern. What do you expect? She made proper tea, and was gracious in understanding that we stopped listening to her mid-passage. And right as I hit a wall and had resigned myself to walking back to the hotel for my first real night of sleep in a month, Chris announced that we would be going to a rum bar. Again, his leadership shining through. We found ourselves amongst the locals 20 minutes later, drinking rum, shooting pool, and smoking joints. At 11pm, nearly 4 weeks with these people, and as many hours of consuming Antigua’s pleasures, and I was done. Vince was a gentleman, escorting Vicky and I back to our boat and hotel, respectively. And, with a crooked smile on my face, put there by a sailor’s welcome only Antigua could provide, I laid down to my first full night’s rest in a month. And now it’s 9:44 pm on Saturday night. I am 30,000 feet above the continental US, on my second flight of the day. This one is bringing me home to Denver after a short layover in Miami. I woke up this morning, surprisingly refreshed after a day of uncommon consumption. I think the local’s pharmaceutical at the evening’s end helped - I mean wasn’t ganja invented on the islands? Those guys know what they’re doing. I grabbed my goggles and went to the pool for a 30-minute swim. The exercise was my first in a month and felt so good. After that, I grabbed one of the stand up paddle boards for hotel guests and headed out in the bay for half an hour. I cruised by Falken to check on my friends after last night. Chris, of course, was dangling high up on the mast, fixing the latest ailment plaguing our vessel. Bruce and Mia were bright eyed, but Vicky looked like she had just been run over by a Zamboni. Probably a good thing that rum is illegal in Canada. She needs to stick with Molsen and Celine Deon - Rum punch and Bob Marley are doing her no favors. Back at the hotel, after a brief stretch on the pier, I grabbed a shirt and made it to the hotel restaurant, which offered each guest breakfast with their accommodations. “Would you like a hot beverage, with your breakfast, sir”. I was asked from the smiley islander serving me. “A cappuccino, please” I said with a grin, remembering my new fixation from the trip’s European origins. Some things clearly followed me across the ocean. And as I enjoyed what served as my last beverage on this crazy voyage, I began thinking back to my first, in that little breakfast diner at Gatwick airport. ‘Was that this year’, I thought? The last time I took 4 weeks off from anything was back in college, more than 20 years ago. I’ve read that the most effective way to slow time is to fill your days with unstructured activities, and then journal about them. I’d add that if you throw in a 3,000 mile boat ride, you can slow it even further. And though I can’t remember every minute of the trip, much of my last 30 days comes with easy recollection…but it sure flew by. Looking over the water across the bay to the green hills rising out of the blue, the warm Caribbean breeze kissing my face, I couldn’t help but smile. That moment of quiet reflection. From the long flights and anxious anticipation of arriving in Las Palmas to a week’s long vacation on a Spanish island, meeting new friends, and being indoctrinated to Falken. Then days, weeks, of making a passage. Enduring the heat, the boredom, the proximity of others. Being amazed by the sea life, the stars, the rising and setting sun and moon, the waves, the freedom, the wind. The abrupt chaos of a day and night in Antigua. And the frenzied ending to an epic adventure. I called Tara en route to the airport. We simultaneously said that 4 weeks is too long. I went searching for limits, and I found mine. I don’t want to be gone from my girls for 4 weeks. I don’t want to be on a passage for more than a week. I don’t want to own a sailboat - Chris, dangling high above decks today, post-adventure, was another subtle reminder that ownership is not sailing - it’s maintenance, and tinkering, fixing, and fine-tuning. Not for me. I learned that who you travel with absolutely matters - this was an awesome crew, which made the passage palatable, but having a loved-one on board would make it better. So, the next big adventure? I need some time on that one. On the sailing front, it’s going to look like chartering a catamaran, with family or close friends, for a week, maybe two. And Red Stripes at the end of every day. So many Red Stripes. And rum. So much rum. I’m always surprised and honored to learn that people followed along on these adventures. Like, you read my blog? No way! In an age where our kid’s aren’t the only ones suffering from a short attention span, I know it’s an undertaking to read all of this. I write it for me, honestly. I love to write. But I wouldn’t get nearly the enjoyment if I didn’t know someone else was laughing along, journeying with me. If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. Together, we went. And we went far, didn’t we? We all just did that. Thanks for coming with me.

0 Comments

Where is Royce? Click to sail along! ⛵ It’s 5:30 on our last night at sea. Barring some unforeseen iceberg, Orca attack, or unsupervised helming by our friend Jeff, we will make landfall at first light. It will be Friday morning, 5/12, nearly 18 days after departing from the Canaries.

We are all lounging in the cockpit, as the last of the crew finishes their shower. The event has turned into a spectator sport. I can’t decide if the communal dialogue while scrubbing my privates is worth the open-mouthed stares and picture-taking. Oh well, the dye has been cast. That was the last cleaning - the third in nearly as many weeks. I’m reading a novel set in 10th century, England, where bathing occurred twice a year. Our weekly cleaning would be considered a wasteful extravagance back then, though it seems way too infrequent in our present state of boat grime. But then, we’re not battling Vikings, so are we just wasting water? All hands were on deck for a meeting to discuss tomorrow’s landfall. We covered the short list of cleaning duties to be accomplished, a boat care checklist, flag raising, and quarantine rules. Alejandro clarified for all of us that we need airline flights booked, a hotel reservation lodged, and a note from our parent or guardian before Chris will release our passport and allow us to leave. I wonder if my TSA pre check will allow me to get off this boat faster - I’d hate to be 8th in line to step ashore and order a beer. Mia highlighted that this will be our first landfall: “Don’t let the moment be lost by burying yourself in your phone, now that service as been restored after nearly a month” she said. Something about the comment reminded me of the enormity of what we just accomplished. Though almost overtaken by a squall last night, we encountered very few acute dangers during our crossing. There have been no reported cases of scurvy. None of us were chained and locked in a hold, mid-decks. No injuries outside of my damaged pinky, a few scraped shins, and perhaps a sunburn. Sure we ran out of fresh fruit and vegetables a week ago. Yes, there have been sleepless nights, sweaty bunks, and the occasional short-tempered remark. On the whole, though, the trip was somewhat benign. But, how many humans over the millennia have made that passage? Do we need battle scars or stories of sea monsters, burials at sea or pirate attacks to justify our adventure? In short, does this count? Is the adventure worth sharing with friends or future generations of little sailors carrying our name? Is that long awaited tattoo justified? I’m finding it harder, with each passing year, to appreciate the present moment. I try so hard to recognize a first, or exceptional experience. But it is never as sweet as when time has passed, and I yearn to be back in that moment. Nostalgic for that first. That exceptional. I’m sitting here, watching the little patches of seaweed float past our stern into the oblivion we just covered. I know this is my first, and may be the last time I make this trek. And still, it’s hard to appreciate the enormity of it all. What will I remember most? What will I wish back? What hardship, not yet appreciated, will elevate in my mind and in the stories I’ll tell? Who will I remember and whose face will fade away like the numerous sunsets we observed? What lessons have been learned? Time will tell. Some of the experiences, thoughts, feelings will follow our wake and make landfall with us, bottled-up and stowed safely for future recall. We’ll embody them and they will impact us, perhaps influencing a future path. And certainly there will be moments, conversations, sunsets that will be left at sea. They will remain, lost in our wake. “Land Ho!” Chris announced. I look, and sure enough. A small piece of land, two peaks, emerging from the sea some 30 miles off our bow. It’s 6:32pm, almost exactly 18 days after departing. All of this contemplation has to wait. I have some packing to do. And a tattoo to design. Where is Royce? Click to sail along! ⛵ The sun is so bright,

Land birds arriving in sight. This is our last night. 11:30 in the afternoon. I’ve jury rigged the end of a halyard line, to harness myself into the cockpit seat on the high side. When a wave lifts up Falken’s stern, and tries to dump me onto the floor, I’m held in place…ish. “Hey Einstein. Hey Einstein.” Staton calls from the helm. “Yeah?” I respond, guarded. “Why don’t you relocate to the low side.” He’s right. With his erratic driving, it will take more than a few line wraps around my waist to avoid a crash landing on the floor. And I’m still shell shocked from last night. I had just taken a military shower - defined as bathing myself with dude wipes. I washed my face, slicked back my hair, and suited up for one of my last dates with Falken. An evening of helming under the stars and then rolling over and going to sleep - she so gets me. My attire had been waiting patiently for weeks to be donned. Thin performance pants and my favorite button down flannel, that says “I’m comfortable on a boat AND totally into Pearl Jam”. I was the bell of the ball. A few of the crew cat called on my way to the cockpit - or was that just Mia? And not three minutes after sitting down for dinner, a rogue wave crested the side and embraced me in an unsolicited hug, my fresh bedtime attire instantly drenched. I jumped up, lost my footing, and crashed to the low side, in a compromising position between Staton’s legs. Ignoring his lascivious smirk, I stood up and took stock. My finger was bleeding, and I could measure my pulse by the throbbing in my fingernail. Ignoring the doctor’s concern, I stared down the helmsman, Bruce, and retired below with the little dignity I had intact. So, thanks for the advice Staton. I will take the low side, and hope you don’t pull one of those Y turns again, putting me back in harm’s way, or into another crew member’s lap. We’ve talked about this, man. I’m not that kind of girl. So, friends, we are about 200 miles from Antigua. Our speed is still such that we can cover that distance in a day, but now begins the game of jibing and tacking, easing and pulling, trying to get our vessel in line with our destination. Had I been a more agreeable crew in the eyes of the captain, perhaps my requests of turning on the engine and guiding this girl home would not fall on deaf ears. By the looks of it, we will get within a stone’s throw of Antigua by tomorrow night, after the lights of the harbor come on, but the neon sign of the border patrol go off. Which forces us to stay in a holding pattern, offshore, sober, for another night. “We can’t enter Antigua at night” Chris reminds me. ‘Dude, you’re not a real captain unless you can ride this thing into the harbor, under sail and a half moon’ I challenge him, in my thoughts. “Understood”, I respond, defeated. But Falken and Poseidon are conspiring to get me over my malaise. Last night was by far the most fun I’ve had behind the helm. Just as advertised in the opening pages of my constellation book, star gazing is like revisiting old friends. I didn’t see Orion, but all my other buddies were hanging out at Zeus’s bar. The Dipper twins, Polaris, Gemini, Scorpious, Libra, the Southern Cross, Mars, Venus…all visible because the man in the moon was asleep and the clouds had whisked away. I saw satellites bustling about, delivering Amazon packages and internet porn. Shooting stars were burning holes in the atmosphere. The waves added a background chorus to the scene, while her phosphorescence reminded us where we had just been, and Venus lured us toward where we intended to go. I was on a surfboard for three hours. The cool breeze erasing my earlier ocean shower. Falken asking for all my attention. Realizing that this would be one of my last rides under a night sky, I checked my heading in the red glow of the compass, gripped the helm, and found my planets to chase through the night. Smiling at all my good fortune…in my second outfit of the night. Where is Royce? Click to sail along! ⛵ Surfing down the waves,

Wind is howling through the shrouds, Flying through the air. We have never covered 200 miles in a day. This will break our streak, 16 days in. We’ve never gone faster. The sailing has never been livelier. And still… Alejandro and I give each other blank stares. We have discussed our lethargy. Our desire to sit. To rest. To cool down. By midday, when the sun is at its zenith, the boat turns into an inferno. To go above decks means to bake in the sun. To remain below, which is usually the decision, you sweat in your bunk trying to get comfortable under your fan. The wet bunk. The heat. The still air. This gimbled oven we’ve called home is now lively because of the higher winds and following seas. What is helping us get to our target faster, is also our greatest torment. The heat, without the shifting boat, pitching and yawing below us, would be too much. Together, they are unforgiving. It’s 4:30 in the afternoon. We lost an hour again today, which only extends the length of our suffering. My roommate and I are sitting at the settee below, the cabin fan aimed at the back of my neck. It’s cooled down a little, coagulating the sweat and sunscreen on my body. I’m sticky. My Garmin watch has alerted me to a “Detraining”Status, whatever that means. It can’t be healthy. I’m already dreading the excited questions I’ll get from friends and family upon Re entry. “How was it”?! “Was the trip so amazing?!” “What was it like out there?!” I’m concerned these last few days of introspection and external suffering will skew my response. How can I possibly sum up more than 2 weeks of an ocean crossing in a manner that excites the interviewer, or gives any credence to its mental and physical demands. I can’t. I don’t have the energy to respond. Earlier today, Mia and Chris were talking about a sailor they know who spent 306 days circumnavigating the Americas, non-stop. “Why would you do that”, Chris challenged? “What are you trying to prove, and to whom, by doing that?”, he added. He’s right. Stopping at all of those countries along the way would make for a more rich experience, and less of a hardship. But then, why climb a mountain, or complete an ironman, or sail across an ocean? I suppose to have survived the hardship of it. Stand at the summit, the finish line, the beach - look down, or back, or across and be proud of your accomplishment. Tell your friends how hard it was. I’m feeling like it’s mile 23 of the the marathon. So close to the tape. It’s no longer a physical journey. You need to will yourself forward. I’ve been there - I know the feeling. The body in absolute pain. It’s done. It want’s to be done. I’m feeling that now. I’m exhausted. Will I ever find motivation again? Will I ever look at another boat and want to climb aboard? Unlike the marathon, I have no choice, physically. I’m going where Falken goes. But now is not the time to give in, mentally. Overlook the heat, the exhaustion, the lethargic indifference. Try to soak it up - it’s coming to an end. I started my 4th book yesterday. I can’t figure out this new Kindle - I never know how much progress I’ve made or what chapter I’m on - how much farther do I have? I’m just in there somewhere. Swept up in the story - a wave pulling me along. Similar waves are bringing this adventure, this marathon, this hardship to an end. I can picture the beach. I can taste the beer. I can imagine the feeling… I just crossed an ocean, and it was good, I’ll tell my friends. Where is Royce? Click to sail along! ⛵ I reach for her hand,

And dancing through the warm night, I guide her to land. It’s 10:45 on a Monday morning. We set our clocks back an hour today and will do so again tomorrow. In international waters, we can manufacture our own time, and when it should change, but need to arrive in the Caribbean under the formalities of civilization. Another reminder that the passage is nearing it’s end. As that conclusion approaches, and I was helming this morning before a rising sun, it occurred to me that I’ve done little to help the reader appreciate the main character of this story - Falken. Yes, you understand her functions, and through accompanying pictures or video, you might get a sense of her layout or her features. But do you really know her? How she feels, cutting through the waves? Or how she makes me feel, behind her helm, leading her daily in a dance with the Atlantic? Shifting winds, and cresting tides forcing a new step, like changing music. Mother Nature has been in absolute control of the playlist from the outset, and despite our strong desire to change tunes, our requests are never considered. We must simply dance the steps she demands across her watery floor. But, as Falken and I fell into rhythm this morning, as we have for more than two weeks now, I haven’t discussed the relationship I’ve built with this sailing nymph. If it’s possible, my heart beats fastest, when I wake up on a Saturday, rollover in bed and observe Tara sleeping next to me. Her angelic face, peacefully at rest, is unstressed by the chaos that awaits her when slumber ends. If one of our kiddos didn’t end up in the bed overnight, which is more common than not, we are alone, together, and I just watch her breathing. Now, before you get all “dude, that’s creepy, lurking over your helpless bride”, just appreciate that feeling. It is a deep sense of love and tenderness that washes over me. It’s with a similar tenderness, that I step behind the helm of Falken, two weeks in. I know how she’ll respond when a wave approaches her beam, or how she wants to turn into the wind when a gust surprises us both. We’re dancing. Last night, the moon, still asleep below the horizon, left a black canvas for the stars to consume. Shining down from their dark expanse, they sparkled across the water - Zeus’s’ disco ball lighting the floor. Rather than steer toward a star off her bow, I simply guided Falken’s main sail between Venus and Mars, and watched her white dress dance between the two planets. We understood each other. I led, but she moved gracefully through the waves, knowing the steps, and dancing along. Today, we are making better time than the last several days. The joke that we are consistently 6 days away from Antigua is losing its humor. We are certainly getting closer, and although the crew and I equally share an anticipation for arriving, there is this pit in my stomach that I’ve noticed, born from the next dance with Falken approaching my last. The beauty in knowing we are nearing our end, allows me to be that much more attentive to her each time I take her hand. Do I exercise that same light touch, and appreciation for Tara, I wonder? What if I knew this morning might be my last with her? Would I cherish the moment more? Do I appreciate her as much as I should? This absurd adventure, that she supported from the start, certainly takes its toll. Though Falken can dance through the night and on through the day, week’s on end, her partner needs a break. I can sleep. I can eat. I can rest, before guiding her once more across the floor. Raising four children was never a one-helmsman’s role either, and yet I’ve left my partner alone to dance around all the complexities of life on land. She is so deserving of a rest. I am living in this dreamlike state at sea, soaking up all that I can from the trip, from Falken and the commencement of our relationship. But I’m yearning to return home, to that sleeping nymph next to me, who slowly opens her eyes, and smiles. |

We're the Zimmerman Family!

Home Base | Denver, CO A family of six that

LOVES to sail ! Follow our crew (Royce, Tara, Avery, Charley, Nora & Ruby) as we blog our sailing adventures Current Trip:

Set Sail 4.22.23 | Las Palmas - Across the Atlantic - Island of Antigua Previous Trips: Set Sail 9.22.21 | Sweden - Germany - United Kingdom Set Sail 7.18.19 | Newport, RI - Martha's Vineyard, MA - Nantucket, MA - & back! Thanks for reading !Previous Trip Posts:

April 2023

|